Or how to tell t’other from which, as they used to say in Lancashire. They might still do, actually, but I digress …

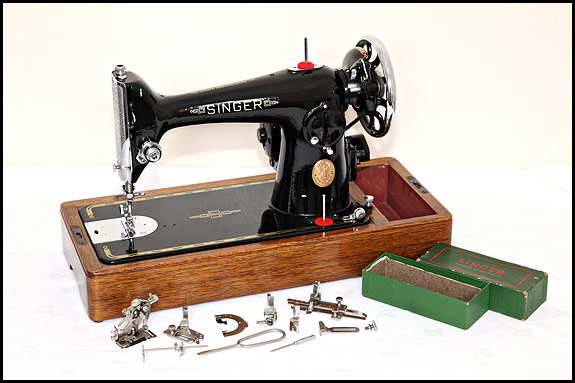

If you’re on the phone to somebody who’s put a for sale ad in the local rag which just says “Old Singer sewing machine for sale” or something equally informative, you obviously need to know a bit more about what exactly it is that they found in the attic when they moved in and now think might be Worth A Few Quid. If you’re lucky, they might have put a picture in the advert. And if you’re really lucky, it might not be a lot worse than this specially-taken rubbish snap.

Before we go any further, though, A Word Of Warning. On a very hot and incredibly humid summer afternoon, I once drove for well over two hours through horrendous traffic to buy a Red Head. That’s a rare-in-the-UK Singer with distinctive decals which I think are OTT but Elsie thinks are lovely. I’d talked about it on the phone to the person selling it, and I was fairly sure of its condition. We’d agreed a price. When I got there, I was ushered into the kitchen and shown the machine. It was a clapped out and very ordinary early 66 with the most boring decals Singer ever used, and those in a very poor state.

“Hang on” says I. “This isn’t the machine in the photo in the advert.”

“No, but does that matter? They’re all much the same.”

“Are you serious?” says I. “You don’t have the machine you advertised?”

“Well I couldn’t find my camera so I used a picture I found on the internet. I can’t see it makes that much difference.”

There’s not a lot you can say to that, so I just bid her a cheery “Die soon” and drove over two hours home to Elsie and a large glass of Merlot. The moral of this story is

ALWAYS ask the advertiser if the picture in the advert is a picture of the actual machine for sale

So, getting at last to the point of today’s epistle, I’ve evolved a standard way of extracting the information necessary to identify a machine on the phone, and it seems to work. Believe me though the process can be a bit like pushing jelly uphill with a fork at times, particularly if the advertiser’s getting on a bit and doesn’t hear so well, or their attention is split between me, their sewing machine, the television and what sounds like a shedful of kids running amok.

But whatever. What follows only works for the common domestic Singer machines produced in the UK between around 1900 and the mid-1960’s, and it only enables you to identify the basic type. If you need to know whether the article in question is a 15-88 or a 15-91, for example, this is not going to help you one bit. But if you want to know if what they’re selling is a 127 or a 201, or even if you just want to know what Grandmother’s old Singer is, stick with this and with any luck you’ll soon be able to tell.

The person on the other end of the phone needs to be looking at the machine in question as if they’re using it, that is to say with the big wheel end to their right and the end with the needle to their left and no, that’s not patronising. Always remember that whoever’s looking at it might be completely clueless! Besides, check out a few snaps of sewing machines for sale and be amazed by how many have been photographed just like that picture above. So, here we go – but first Another Warning …

You cannot identify a machine by what it says on the cover of its instruction book

Even when the owner swears blind it’s the original one which came with the machine when Mum bought it off Auntie Marjorie in 1953. I don’t know how anybody’s supposed to actually know stuff like that, but I do know that you quite often find that the owner of a 27 or whatever is totally convinced it’s a 99 simply because there’s a 99 instruction book in the compartment in the base. Anyhow, here we go …

1. If you look at the vertical column of the machine, just above the bed (the flat metal base), there’s a round-ish metal Singer badge. Is there a small rectangular metal plate with two or three numbers and one letter on it just below that badge? If there is, the number on that plate is the model number and your problem is solved. If there isn’t, read on.

2. If the tension adjustment knob (the one with those discs and the springy thing behind it) is on the metal plate on the very end of the machine and it faces left, the machine is a Model 15. If however the tension adjustment knob is mounted straight onto the black metal of the machine and faces the user, it isn’t a 15 so we need to dig a bit deeper.

3. It will either be an early machine of the “vibrating shuttle” type which takes a long thin bobbin, or a later machine which takes a round bobbin, so look at the left-hand side of the machine bed. If it has a small round plate under the needle and two rectangular plates which run from front to back and meet up in the middle, it’s a vibrating shuttle machine. If instead it has a D-shaped plate under where the needle is and a more-or-less square chromed plate at the left-hand end of the bed, it’s a round-bobbin machine.

4. If you’ve established that it’s a vibrating shuttle machine, measure how long the bed is. If it’s getting on for 15 inches, you have either a 27 or a 127. If it’s nearer to 12 inches, you have a 28 or a 128.

5. If the bobbin winder thingy on the right is about 2 inches above the bed, it’s either a 27 or a 28. If the bobbin winder’s higher up, roughly in line with the middle of the handwheel, it’s probably a 127 or a 128. So for example a long bed machine with a low bobbin winder is a 27, and a short bed machine with a high bobbin winder is a 128. OK?

(The bobbin winder position isn’t conclusive, simply because there were some transitional models made and some 27’s and 28’s have had their low-level winders replaced by a “high-level” one at some point in their life. However, if the machine’s got the higher-up bobbin winder and there’s a round metal button on the shuttle carrier which ejects the shuttle when you press it, you almost certainly have either a 127 or a 128.)

6. That takes care of the vibrating-shuttle machines. Moving on now to the later round-bobbin machines, if it looks “old fashioned”, it’s all metal, it’s black and it’s not a 15, it’s almost certainly going to be a 66, a 99 or a 201. Does the spool pin on top of the machine upon which you plonk your reel of thread go into a chromed steel plate about 2 inches long with rounded ends? If so, it’s a 201. Specifically, it’s what’s referred to as either a 201 Mk1 or an “early type” 201.

7. If the machine is black and there’s no chromed plate under the spool pin, is the bed of the machine about 12 inches long? If so, it’s a 99, which is perhaps the vintage machine most commonly seen nowadays still in reasonable condition.

8. If the bed’s about 12 inches long but the machine is beige/brown and the oval Singer badge is on the same rectangular metal plate as the stitch length adjustment lever, it’s either a 185 which is OK because that’s basically a tarted-up 99, or it’s a later 275/285 which is basically naff. The quick way to tell them apart is that if both the stitch length adjuster knob and the lever which raises the presser foot are plastic, it’s a horrible 275/285.

9. If the bed’s about 15 inches long, there’s no chromed plate under the spool pin on top of the machine and there’s no small plate with a model number on below the metal Singer badge, you have a 66. That’s the big sister of the 99.

10. If the machine looks fairly modern, the top of it’s more or less flat, there’s no chromed metal plate with rounded ends under the spool pin but it still says “201K” under the Singer badge, it’s the later type 201 which is usually referred to as the Mk2.

If you’re still scratching your head, odds on it’s a later machine or an industrial, or possibly a 19th Century one. Most of those will be outside our territory, but by all means send us an email at sidandelsie @ btinternet.com without those spaces if you’re stuck and we’ll see if we can help you solve the mystery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.