Thanks to Syd McDonald who kindly allowed me to scan his copies of them, I can now present for your delight both the Singer Illustrated Catalogue for 1933 and its accompanying Price List. There’s links to PDFs of the scans at the bottom of this post, but while you’re here, let’s just take a quick look at some of the contents.

Before we do though, here’s a few comparisons between then and now to help put prices into perspective. In 1933, the UK average wage was £3 12s 0d (£3.60) a week and a pint of beer cost 6d (2.5p). Today, the corresponding figures are £504 a week and around £2.90, so wages have risen faster over the last 79 years than the price of beer has. What I find quite remarkable though is that in 1933, a typical 3-bedroom house sold for £360, which was just less than two years’ average earnings. Now the average 3-bedroom house costs £243,000, which is over nine years’ average earnings. How come?

Whatever, it seems that life expectancy for women in this country has gone up from 60 in 1933 to 81 now and for men from 53 to 78, so it’s not all bad …

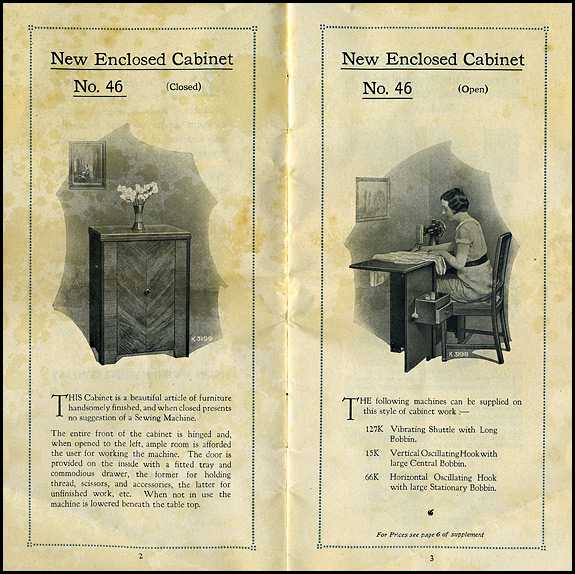

We start with the New Enclosed Cabinet No.46, which should be of particular interest to those who can never remember which cabinet is the 46 and which is the 51. As you can see here, the 46 is the one with the one-piece door with the rectangular drawer on the back of it. The later cabinet which is the same size and shape but has the two doors and the D-shaped swing-out drawer thingies on the back of the left-hand one is the 51, which Elsie and I much prefer. In our opinion, a nice 51 cabinet with modern castors under it and a properly set-up treadle mechanism driving a 201 on top of is a very fine thing to have in the house.

In 1933 you couldn’t yet buy a 201, but a shiny new 66K in a No.46 cabinet could be delivered to your door for a list price of £23 10s 0d (£23.50), which was more than 6 weeks’ average wages before tax.

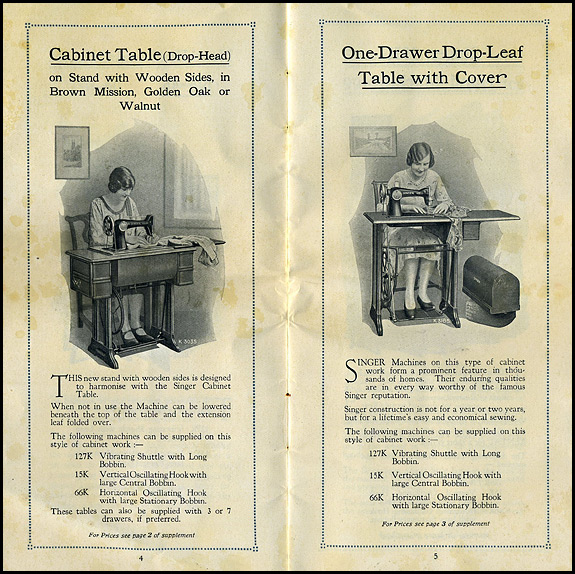

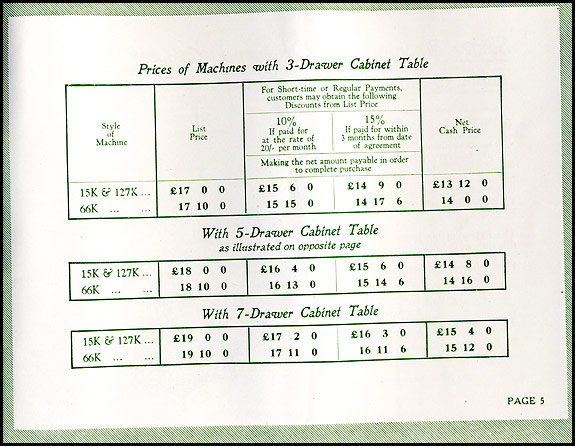

On page 4, we see that by now the old cast-iron legs of the Cabinet Tables have given way to the new wooden sides. A 66K in a 5-drawer base like the one on page 4 was £18 5s 9d (£18.29) if paid for at the rate of 10/- (50p) per month, but could be had for just £15 8s 0d (£15.40) cash if you’d come into money.

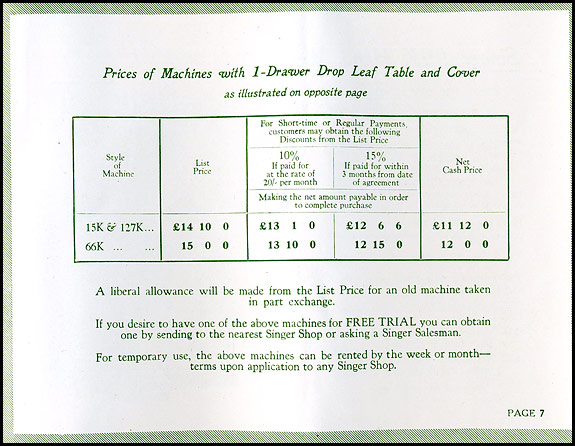

Those Cabinet Tables are still quite common in England, but the One-Drawer Drop-Leaf Table on page 5 certainly isn’t. Does anybody know for sure if that’s the one in which the machine sat in the table in the wooden base which has the slot between the two belt holes so you could just lift the whole thing out and use it as a portable?

There’s no mention of either of these Cabinet Tables (or indeed of the 46 Cabinet) being convertible for use with an electric machine by means of the motor controller 194386 on its associated bracket, so I’m still no wiser as to when that was introduced in the UK.

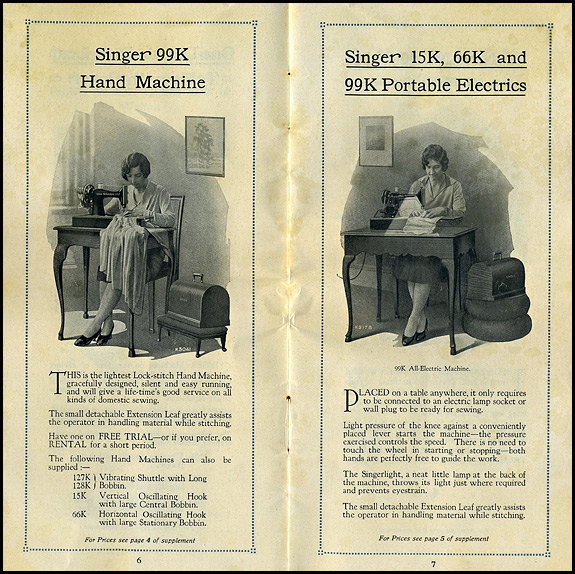

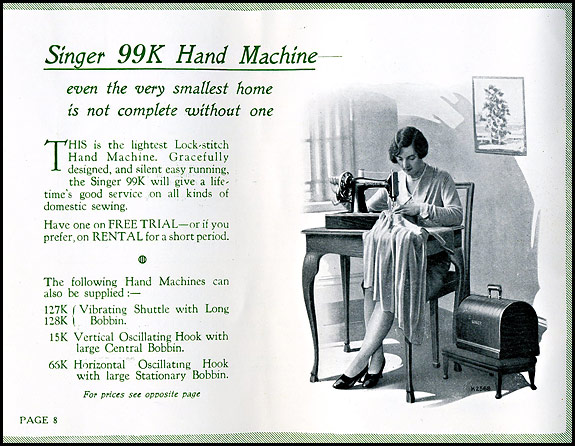

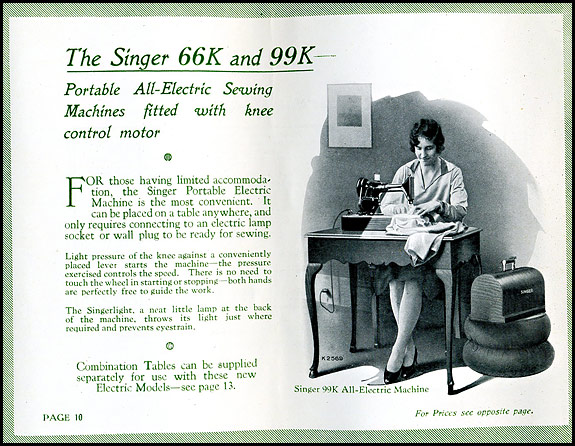

I do love these illustrations of the portables. It seems that Singer could never come up with a convincing way of including the lid in a picture, so here we have it on a footstool of just the right size and shape on page 6, and on what I’m convinced is a pair of wheelbarrow tyres on page 7.

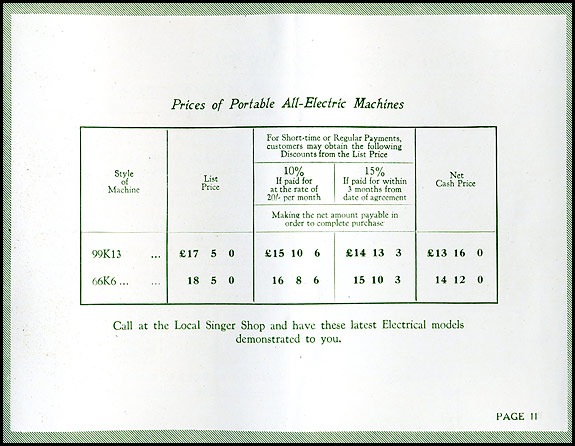

A nice hand-cranked 128 portable would have set you back £9 17s 6d (£9.87) in 1933, although for just thirty bob (£1.50) more you could have had its full-size sister the 127. A knee-lever 99K electric, on the other hand, was £14 if paying cash. That price included a Singerlight, but not a footstool or the tyres to put the lid on.

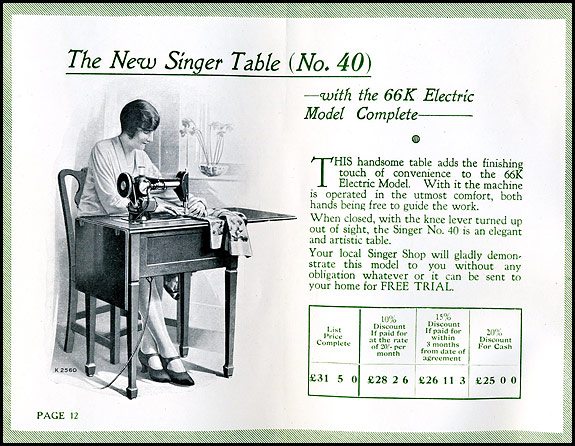

And now we have a knee-lever 66K electric in The New Model 40 Table which, it says here, is an “elegant article of furniture”. Be that as it may, have you noticed how the word “article” in this sense seems to be obsolescent nowadays in much the same way that “apparatus” does? It’s a shame. They’re both fine words.

Model 40 tables are decidedly uncommon nowadays, and I have to admit that as far as I’m concerned that’s not a bad thing. £31 12s 6d (£31.62) on Easy Terms, or £25 6s 0d (£25.30) cash to you, Madam. That was getting on for two months’ average wages …

The all-steel foot controller shown here on page 10 is a rare bird now too, which if you ask me is just as well because they’re a bit on the primitive side – and they do tend to stink when they start getting warm. Note how the mains lead is supplied with a bayonet connector on the end so that when you’d fitted the motor to your machine, you could plug it into any convenient light fitting once you’d taken the bulb out of it.

Any reader raising an eyebrow at that last observation might care to note that plugging a sewing machine (or a hairdryer come to that) into a table lamp or other light fitting was common practice at one time. When many rooms had only one mains socket in them (or at best a pair of them side-by-side on the skirting board), table and standard lamps often served as extension leads, and most households were possessed of an assortment of plug adaptors by means of which many light and power problems could be solved.

On page 11 we note that in 1933 the 15K was the “Dressmaker’s Machine”, and that the base shown is the “artisan” one with the bigger-diameter treadle wheel to facilitate higher stitching speeds.

And finally a couple of industrials. Note the cast-iron legs, which were by now obsolete as far as domestic customers were concerned. Note also the convention whereby women sew at home on domestic machines and men sew at work on industrials.

I don’t know anything about the 31K15 apart from the fact it’s got a knee-lifter, but that back leaf of the table certainly does look handy! The 29K53 is a fascinating machine that’s often referred to as The Patcher, and its variants always seem to sell for a decent price on Ebay nowadays. I love the way you can sew in any direction with it, and alternate between treadle and hand drive. It’s a very clever bit of engineering.

For scans of both publications as PDFs, click on the links below. I did them as two separate files so you can, should you wish, have the catalogue and the price list open at the same time for ease of cross-reference …

1933 Singer UK Illustrated Catalogue

By the way, lest any of our overseas readers be confused by the bayonet connector, I should perhaps point out that not only are we on 220 volt here, but our light bulbs don’t screw into light fittings like yours probably do. Ours have a bayonet cap, about which everything you could ever wish to know is, as usual, on Wikipedia – see here

You can’t buy those bayonet connectors nowadays, unless of course you turn to this guy on Ebay. Those things were often used in conjunction with the Y-shaped two-way adaptor (a picture of which I couldn’t find), which plugged into a lampholder so that two bayonet connectors could be plugged into it. I suppose the theory was that they allowed you to use two light bulbs in one lampholder, but I never saw one used like that.

While I’m on this subject, I should perhaps explain that in England nowadays, you can’t even walk into a shop and buy an ordinary 100 watt incandescent light bulb, the manufacture of which has been banned by the EU in order to save the planet. We’re therefore hoping the 20 that I bought online last week will see us out, as we only need them for 3 lights in the house which are used intermittently and for which energy-saving fluorescents are neither use nor ornament.

And if making incandescent light bulbs obsolete as a token gesture in the direction of planet-saving seems daft to you, how about the singularly crazy legislation requiring a proportion of the light fittings in all new homes to be 3-pin bayonet lampholders into which neither traditional bulbs nor energy-saving fluorescents can be fitted? See here

Have a good weekend, folks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.