Before we get stuck in, let me say that there is an alternative way of removing and replacing a head in a wooden base, but you need more of a toolkit to do it that way and you could screw up the finish round the hinge bodies on the base. Besides, this way’s not complicated, it just seems that way when you explain it.

First off you need to slacken the chromed thumbscrew on the base so you can move the little catch thingy out the way and swing the head back on its hinges. Do be careful though, because the head is heavy and if it’s loose on the hinges, it might not move quite how you expect it to. If you’re a bit worried about this, put some kind of padding on the table behind the base such as a folded towel, and at least then if it flicks over onto its back, you’re unlikely to bend anything. Or dink the table.

If you’re confident, all you need is something of such a height that you can lay the head down on it and all will be held at a convenient angle for you to furtle about under the bed. For this lovely 99K which followed us home from Dartford yesterday, a couple of Elsie’s old books was just right (since you asked, the 1931 Womans Own Book of the Home and The Complete Illustrated Household Encyclopaedia) …

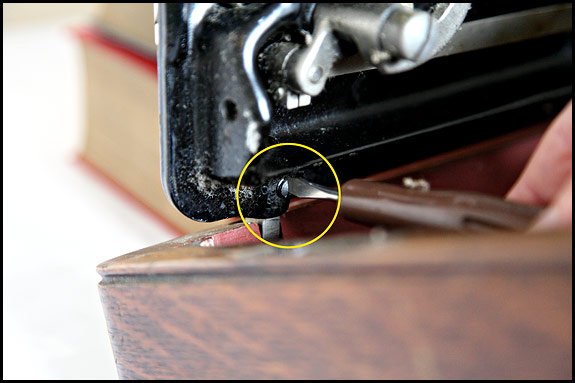

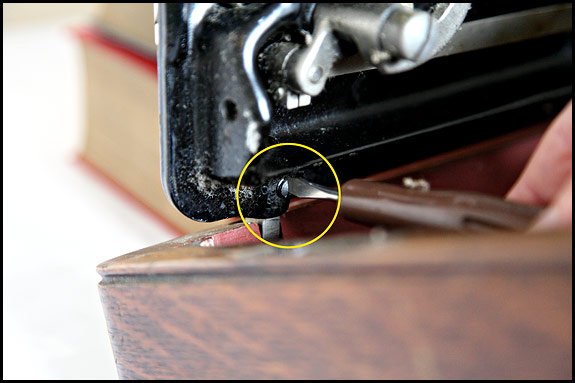

The next step is to locate the two grub screws (for that is what a small bolt without a head like this is called) which lock, or at least should lock, the machine securely to the two hinge pins. Note for pedants – yes, I do know that a grub screw is actually a set screw and not a bolt. Not everybody knows what a set screw is though, so just chill, dude.

As I was saying, you need to unscrew the two grub screws, if indeed they are not already unscrewed. Or missing …

You don’t need to take those screws out, only unscrew them enough so that you can slide the head off two two hinge pins, but if you over-do the unscrewing and they fall out, it’s no biggie because they will (should) just drop into the machine base. Whatever, you can now try lifting the head off the hinges, remembering that you need to take the weight and lift the thing up and towards you at the same time. This is the point at which you wish you’d planned ahead and worked out where you were going to put the head down once it’s out the base, but such is life.

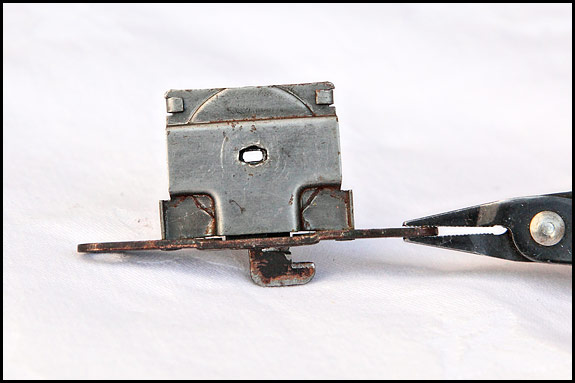

There’s your grub screw unscrewed almost to the point of falling out, and you can see above it the hole into which the hinge goes.

That screwdriver, by the way, is the Singer one which was supplied with some machines, and if you have one of those, you have the ideal thing to do with your grub screws. The blade’s the right size, it’s just the right length, and you can get a good grip on it. Anyhow, having put the head down somewhere sensible, you can now fully appreciate all the little fluff bunnies in the bottom of the base and also ponder on quite how all those pins ended up there.

Now, if you lift those two hinge parts up, you’ll almost certainly find that they fall down again. They won’t often stand up on their own, which could make it really awkward to replace the head in the base without some obliging soul helping you out, because you need to slide both pins into the holes at much the same time. It can be done single-handed, but there’s a definite knack to it. There is though a sneaky way round the problem, for which you need one of those nice red rubber bands which kindly post persons sometimes drop outside your front door on those occasions when they do actually favour you with a delivery …

OK, it doesn’t have to be red, but if it is, it goes nicely with that cheap paint they used inside the bases. Whatever the colour, now your hinges will stay like that while you carefully line them up with the holes in the back of the base, then let the head down all the way on the pins. And if you forgot to do so, it’s at this point that you wish you’d remembered to check whether the two grub screws are in place, screwed in just a turn or two …

All you have to do now is lower the head down carefully until the front of it’s just above the top of the wooden base, then pull it towards you a bit (like 1/4 inch or so) so it rests there rather than dropping down into its final position. You can then cut the rubber band and swing the head up and back again, letting it drop down all the way onto the hinges, then hold it there while you tighten up the two grub screws.

And that’s it! It can be a bit nerve-racking the first time you do it single-handed, particularly if the machine’s a heavy old cast iron 201, but hopefully now you know what’s involved, you can at least see that it’s possible. Having said that though, I’m the first to admit that another pair of hands makes things so much easier …

You must be logged in to post a comment.