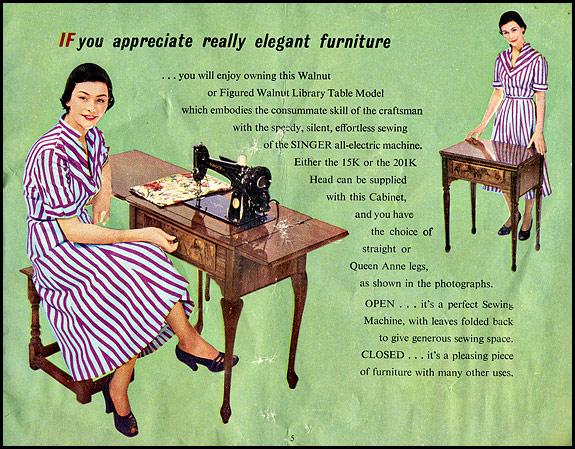

OK, here’s the rest of that wonderful Singer brochure featuring Ann Droid and her stripey frock, and thanks to Alison we now know that this was almost certainly published in 1951. Our copy’s somewhat faded in places 60 years on, which is why these scans aren’t all that brilliant …

“Do you prefer cabinetwork of contemporary design?” indeed! As far as we’re concerned, the best thing about these Cabinets, which we always thought were Tables, is the fact that the legs are readily detachable. That’s a real boon when the machine you just brought home is in one of these things and you can’t quite bring yourself to take the table down to the dump recycling centre once you’ve taken the head out of it, so the only place left for it is in the attic alongside the other two.

Having said that, Elsie’s determined to get one of them down from the roof soon and take it with us next time we do a boot sale – unless of course by publishing this post I manage to whip up a demand for them that we’ll be pleased to meet. Which I very much doubt, but I live in hope.

Be that as it may, we’ve now got to the middle of the brochure, and because of the way the centre pages are laid out as a double page spread, it just doesn’t work scanned as two separate pages. I’ve had to link to it here so off you go now for a squint at that.

As you can see there, we’ve moved onto treadle machines, and the choice of head is simple – would Madam prefer a 15 or a 201? According to the printed text, the choice of base was equally straightforward – pick one of three variants of the “modern” (i.e. wooden legs) treadle base – 3-drawer, 2-drawer or 1-drawer.

So far so good. However, the notes added by the salesman (with his fountain pen, of course) muddy the waters somewhat. Judging by his sketch, he seems to have been offering a 7-drawer with wooden legs, to which his note “NEW £46” seems to refer, and that’s interesting because neither Elsie nor I can recall ever seeing such a thing. He’s also made a note of a “drop head with iron stand” at £20, which must surely have been old stock because the printed text actually states that the iron legs “have been superceded” by the wooden ones.

His note at the bottom right-hand says “Dressmakers model table top with cover £15”, and I’m not sure what to make of that because “Dressmaker” in this context was usually Singer staff talk for a 201. Even more puzzling, the top right-hand note says “modern style folding head with 7 drawers £28”, which would seem to relate to that base with the four extra drawers drawn in. But if it does, what’s with that “NEW £46” above it?

If anybody can shed any light on those notes and/or the pricing, do please let us know, but before we leave the treadles I’ll just clear up one thing. There was never a 99 treadle. If you do see one, it’s not kosher. It’s a DIY job.

OK … now we come to another double page spread, but this one does work as two halves …

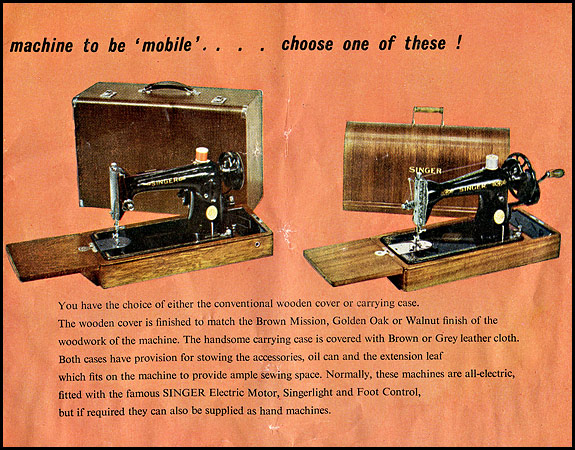

Interesting that one of these “full size machines” is the 99K, which is of course a three-quarter size machine! And how about the claim that they “can be easily carried from room to room”? A hand-cranked 99 in its case weighs 14.5kg (32lb) and an electric 201’s heavier still at 20.5kg (45lb), which strikes me as a fair old weight for anyone to easily carry from room to room.

And look, there’s that “Brown Mission” again! If that’s not a daft name for the colour of a wood finish, I don’t know what is. And was the suitcase-type case really available in grey leather cloth? If it was, did it look as uninspiring as it sounds?

Whatever, note that the text on the page above says “Normally, these machines are all-electric, fitted with the famous Singer electric motor, Singerlight and Foot Control”, yet the 201 illustrated is a knee-lever machine!

Personally I’m convinced that this brochure is 1951, but here’s your proof that it’s definitely pre-1954. If it was any later, Stripey would be wanting to show you her new 222, not the 221 shown here. And at this point I’d better explain for those of you who aren’t Featherweight Fans (or even Pheatherweight Phans) that a Featherweight is either a 221 or a 222.

The 221 was introduced in the mid-1930’s, and Singer eventually made over 1,000,000 of the things. Then in 1954 they brought out the 222, which is just a 221 with a free-arm and feed dog drop, but they only made 100,000 or so of those, which is presumably why they’re sometimes advertised as “rare”.

Incidentally, many of its devotees think the 222 was the first domestic machine with a free-arm, but they are wrong. The Elna Grasshopper was the first, by a good 10 years. But I digress.

I just love the suggestion that a 221 is “easily carried wherever you go – from room to room – on a long trip – or just for an afternoon’s sewing at a friend’s house.” An afternoon’s sewing at a friend’s house? Who is the woman kidding? Or is that code for “so easy to cart about with you to show off to your friends and make them really jealous”? Whatever, Featherweights are undoubtedly cute and they certainly have a huge following with quilters in the States, but for our money they’re over-rated. There. I said it.

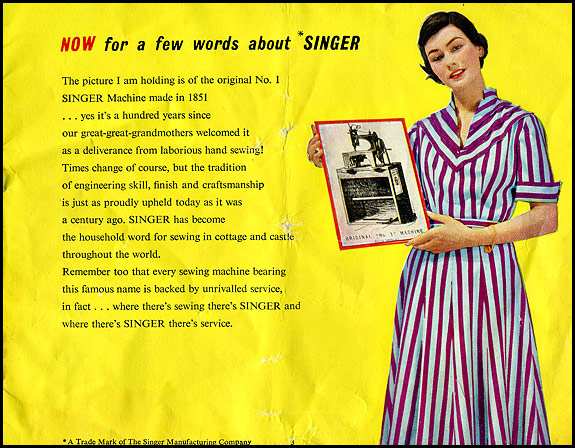

Lovely use of Proper English there, and interesting to think that 60 years ago that wouldn’t have been thought in the least patronising. Or boring. Back then, Singer were still on top of their game. They were the absolute masters at marketing domestic sewing machines, and there’s not the slightest hint anywhere in this brochure of the rot which was soon to set in

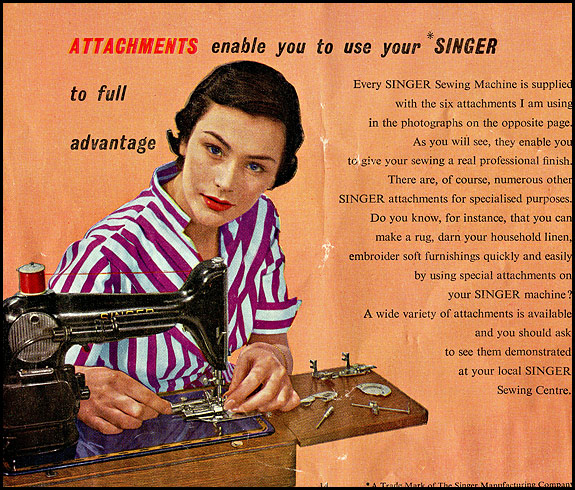

Oh look – she’s doing that sincere expression again, bless her.

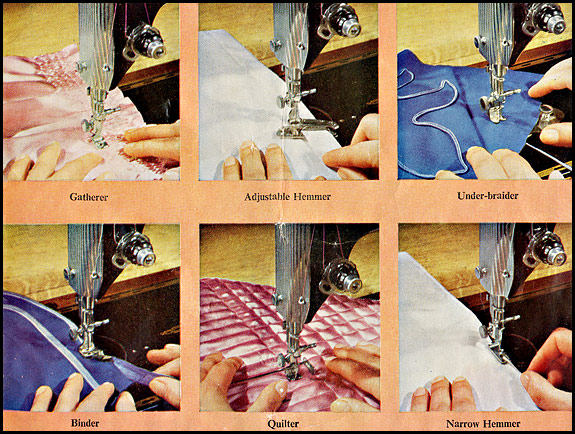

Now, there’s a couple of matters arising from those pictures of the six attachments that were supplied with new machines in 1951 (or thereabouts). One is that, surprisingly, by this time the ruffler was not one of the standard attachments. And the other is the quilter. I really do wish they’d called it what it is i.e. a quilting guide. So many people seem to think that “the quilter” is some awesome attachment which does something really clever, when all it actually does is allow you, within certain limits, to sew parallel to and at a fixed distance from the last line of stitching in your quilt.

And finally we turn to the outside back cover …

with its cutaway of Mission Control. Which raises an interesting question – when did Singer shops in the UK finally stop offering the dressmaking courses, and for that matter the finishing service? If you happen to know, we’d love to hear from you.

Going off at a tangent now, when I first saw Stripey’s frock it immediately reminded me of a silly idea that Kodak UK came up with in the mid-1960’s. They thought it would be fun (or whatever) to have the women who worked in the shops which shifted the most Kodak films wearing very loud blue and white stripey frocks with a yellow Kodak badge on the left breast during the summer film-buying season.

At the time, my mother was one of those women, and I have this vivid recollection of her coming home from work one day with this large brown paper parcel in the wicker basket on the front of her bike. She was not happy. It was very nice of Kodak to give her two cloth badges, a pattern and more than enough material for two dresses, but if nothing else, when did they suppose she was going to find the time to make them?

If I remember rightly, she eventually got a neighbour to knock one up, tried it on, decided she wasn’t going to look like a deckchair for Kodak or anyone else, and that was the end of that …

You must be logged in to post a comment.