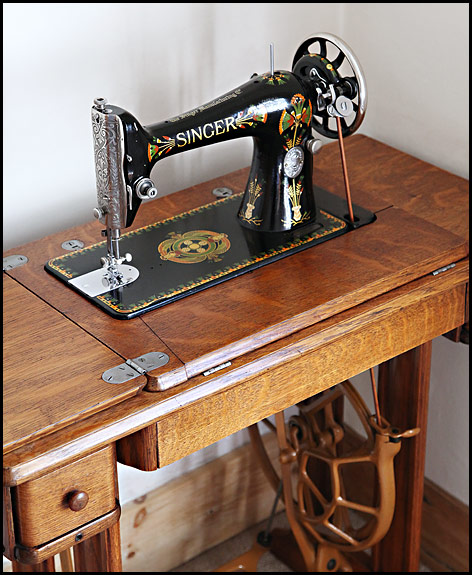

According to the old Singer parts lists, that big spokey wheel on the end of your vintage Singer is the balance wheel. According to most folks who use a vintage Singer it’s the handwheel, so it’s the handwheel as far as we’re concerned here, and we’ll be looking at its removal and replacement, with a bit of a detour on the way.

But why, pray, would anyone want to take the thing off? Well, you could be taking a machine apart because it’s in a disgusting state and cleaning it will be so much easier if you take off some of its bits. Or maybe you want to change the handwheel for a different one? You’re bored and it might be more interesting than cleaning the oven? Who knows. Whatever the reason, people do take their handwheel off. Oh yes. Then they put it back on, and the funs starts when they find that the clutch doesn’t work.

“The clutch?” I hear you say. “What clutch?”

Well, the clutch is what lives behind that big chromed knob in the middle of your handwheel, and without the clutch your machine would be nowhere near as user-friendly as it is. That chromed knob is what is properly called the stop motion clamp screw, and it’s called the stop motion clamp screw because that’s what it does. It stops the motion and it clamps things together.

When you hold the handwheel and turn the stop motion clamp screw clockwise, as you do for normal use, it clamps the handwheel to the shaft onto which it’s fitted, so that when the handwheel turns, so does the shaft. On the far end of that shaft is the linkage to your needle bar, which goes up and down as the handwheel turns.

That upping-and-downing is the motion, which you stop by unscrewing the stop motion clamp screw when you want to wind a bobbin. Unscrewing it stops the motion at the far end of the machine, so that your handwheel can drive the bobbin winder round and round without also driving the needle up and down.

Most people call the stop motion clamp screw the clutch knob, because unscrewing it disconnects the drive in the same way that pressing your foot on the clutch pedal disconnects the drive to your car’s wheels. Let’s take a look behind it …

To do that, you need to remove the stop motion clamp screw, and you do that by first unscrewing that small screw in it. But don’t unscrew it too far, or it will fall out and roll under the table, you won’t find it, and next time you Hoover it’ll be gone forever. Unscrewed about as far as in that picture is plenty far enough. If you can now unscrew the knob, that’s what you do. The thread on it’s about 6mm long, by the way. If you can’t unscrew it all the way so that it comes off, back that little screw out another half turn and try again.

As you take the chromed knob off, one of two things will happen. More often than not, a steel washer-type thing will fall out from behind it. Sometimes though the washer stays in place, in which case what you see when you take the knob off looks a lot like this …

So how does it all work then? Well, it’s one of those things which is a doddle to expain if you’re sitting next to me with a machine in front of us, but trying to explain it on the interweb is not so easy. Fear not, though, gentle reader. We’ll manage. Make yourself another coffee, maybe even grab a biscuit if you’re not still on the diet, then take what follows one sentence at a time.

In the picture above, you’re looking at the end of the shaft which runs through the arm of the machine. Two projections on the inside of that washer engage with slots in the end of that shaft, so obviously when the shaft goes round, so does the washer. And vice versa. Note that the handwheel is fitted on the same shaft. It doesn’t go round with it, though, because it’s not fixed to it.

If you gave that handwheel a spin, it would just rotate on the shaft, which would stay put, as would the washer (if you put a finger on it to stop it falling off the end). Just to labour the point, there’s no connection here between the handwheel and the shaft, so turning the handwheel isn’t going to turn the shaft, which isn’t going to move your needle up and down. As shown in that picture, the motion is stopped. That’s how things are when you’re bobbin-winding.

Now, if you replace the stop motion clamp screw (the chromed knob) and tighten it up, you’re back to normal – rotation of the handwheel drives the shaft which drives your needlebar up and down (and your feeds dogs backwards and forwards). That happens because tightening up the stop motion clamp screw clamps the handwheel to the shaft, so that whatever’s turning your handwheel also turns the shaft, and you can start sewing.

And at this point, anybody really thinking about this is going to be wondering exactly how the clamping of handwheel to shaft comes about, because it certainly isn’t obvious. Here’s how …

That’s an exaggerated cross-section through the clutch area, and this is a simplified explanation. The purple’s the chromed knob, and the red’s the important bit – the stop motion clamp washer. In the diagram, the knob is unscrewed as for bobbin winding i.e. the motion is stopped. Nothing’s held tight against anything, so when the handwheel turns, it just spins round on the shaft, which stays put, as does the washer and the knob. All that happens is that the handwheel turns on the shaft. Nothing else moves.

As we saw earlier, the washer is connected to the shaft by those two projections which sit in slots in the end of the shaft, such that if the washer turns, the shaft must too. Those two projections are so arranged that while the washer can’t rotate about the shaft, it can move along it, but only very slightly.

Now imagine that purple knob being shoved hard over to the left, so it closes up the tiny gaps between itself, the washer, the handwheel and that step in the shaft, and squashes everything tightly together. Squash hard enough, and you have a handwheel which is clamped to the shaft.

In practice, your stop motion clamp screw does the squashing. Tighten it up, and handwheel, knob, washer and shaft effectively become one, so turning the handwheel turns the shaft which makes your needle go up and down. That’s what happens every time you change from bobbin-winding back to normal sewing, and the key to it all is that washer.

OK, that’s the theory and the practice of the clutch, and by now your head probably hurts. Mine certainly does from trying to explain it, so we’ll knock off here and continue in part two …

You must be logged in to post a comment.