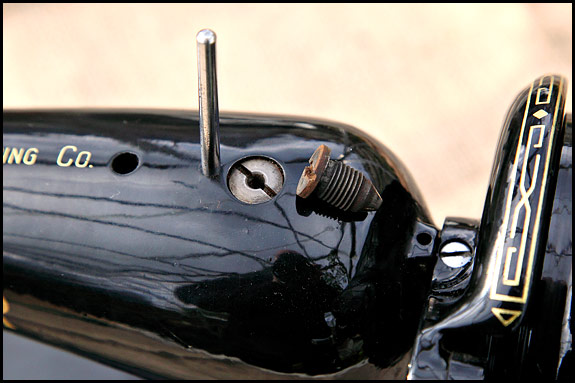

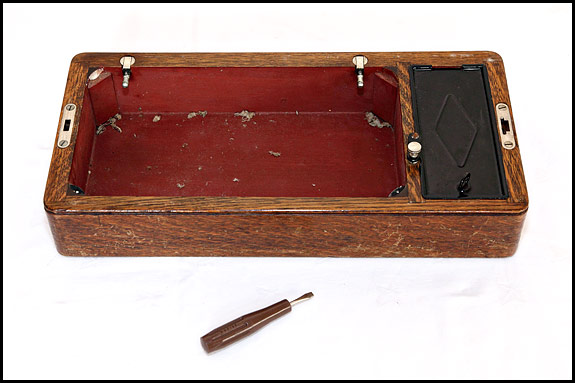

I really hadn’t reckoned on doing this post, but on Sunday morning Elsie and I bought a 201 from a nice lady who told us she got it years ago to make some curtains. But she never got round to making them, or for that matter, anything else. In fact, she never used the machine. Never even had a quick go on it when she got it home.

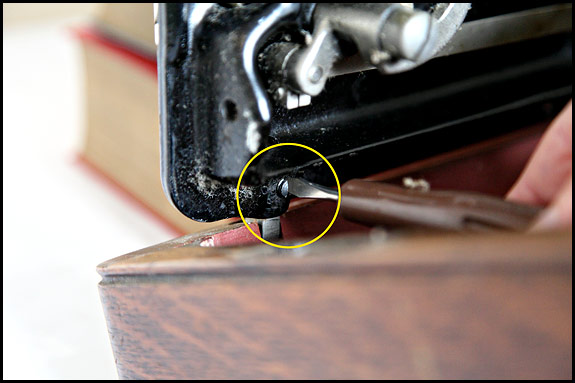

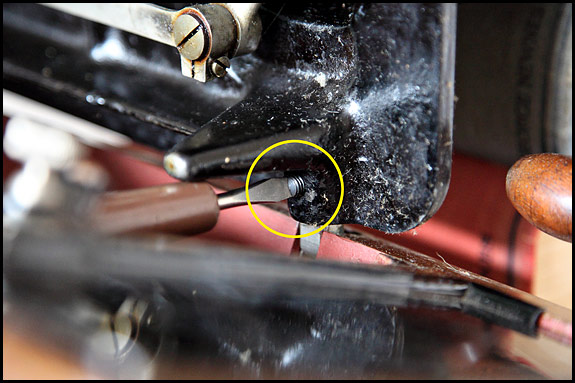

Which is just as well really, because look what we found when we took the mains leads and foot pedal out the case …

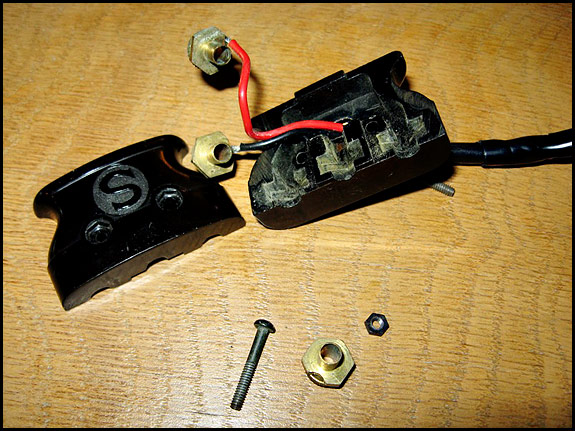

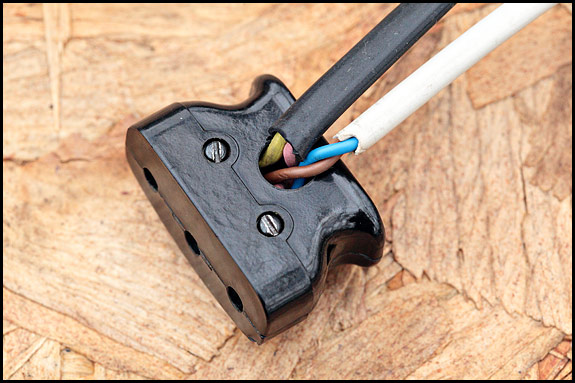

Now, in case you’re not familiar with old electric Singers and you haven’t read either of the last two posts on this subject, that’s the plug which plugs into the socket on the machine. One of those brown leads goes to the foot pedal, and the other one goes to the mains plug.

When you switch the mains on, all should be well providing you’ve got that plug plugged into the machine properly. If, however, you were to pull this particular plug from the machine without first switching off at the wall socket, and you happened to touch one of those sticky-outy bits, you would at best get a fright. At worst, if your house electrics were in need of modernisation, you could get a potentially fatal electric shock.

In the picture below, the plug is connected to the mains and the “245” showing on my meter is the voltage at those exposed contacts …

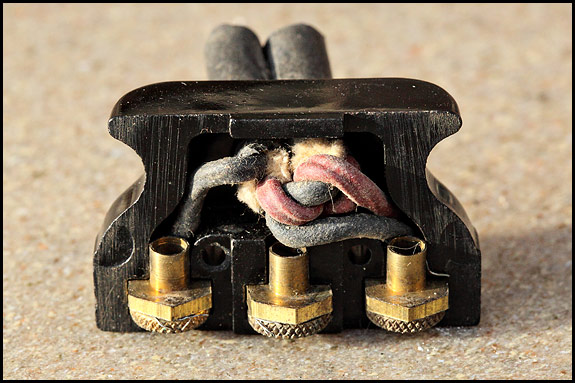

That plug has not just been put back together incorrectly after it was dismantled, it’s been put back together in a way which beggars belief.

That actually takes a lot of doing. How do you forget which way round those contacts were when you took the plug apart? Why, when you connect each wire and bend it back like that, don’t you wonder why each of those contacts has a little cutout in it which the wire could sit neatly in, but it’s on the wrong side? Why has the plug body got those depressions in it which are exactly the right size and shape to accomodate the tubular parts of the contacts which you’ve just put in facing away from them? But above all, how come it never occurs to you when you put it back together that the plug doesn’t look like it did before you took it apart- and it now has exposed contacts which are obviously going to be live when connected to the mains?

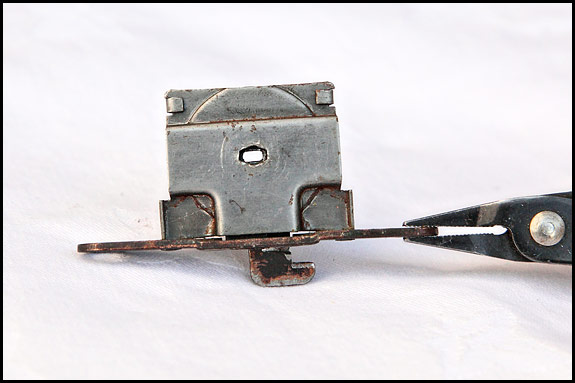

Above, contacts as assembled by our man. Below, contacts the right way round, fitting snugly in the depressions in the plug, and with the cutouts for the wires now usable.

I’ve seen some very dodgy re-wiring on old sewing machines, but how this one came to pass is way beyond my understanding.

Anyhow, having succeeded in writing this post without using the words “incompetent” or “muppet”, I’ll quit while I’m ahead and save how he re-wired the foot pedal for another time …

You must be logged in to post a comment.