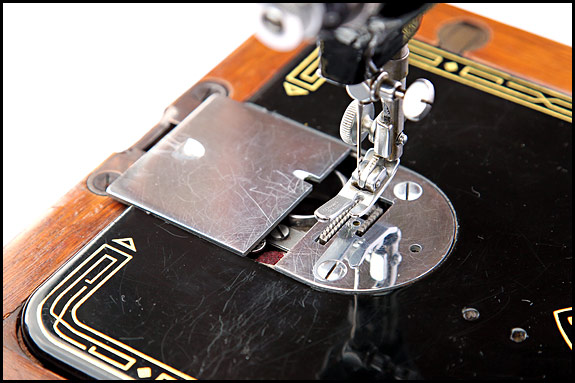

The slide plate is the chromed steel plate which slides open to reveal the bobbin in its carrier. Some folk call it the bobbin plate but it’s not – it’s the slide plate, and judging by the number of vintage Singers out there without one, a lot of people force it off, can’t get it back on, and lose it. Here’s how not to do the same thing yourself.

For starters, let’s see how to remove it, and in the process, discover why you can’t (or at least shouldn’t be able to) slide it right off …

There’s the slide plate slid open a bit, in the same way that you’d slide it open to change your bobbin. To take the slide plate off, you need first of all to turn the machine’s handwheel towards you until the needle is at its highest point. Then, lift the end of the plate which is nearest the needle up a bit (like 3mm or 1/8th inch) against the pressure of a spring which you can’t see. This works best if you only open the slide plate 1cm or so like in that picture, but the main point to watch is that you don’t pull it up any higher than you see in the picture below. All you’re aiming to do is slide the plate over the other one.

There’s actually a bit of Photoshoppery in the picture above because in reality, the plate will only stay like that with your finger holding it up. Anyhow, it’s this next stage which sounds a bit of a faff (or if you’re German, a pfaff) but it isn’t really. Actually doing it is not complicated at all.

Having lifted the end of the plate up a bit, you now need to keep it raised while with your other hand you push the plate towards the needle. What you want is for the slide plate to ride up, first over the other plate (the needle plate), then as you keep pushing it along, over the first feed dog it comes to, like this …

While you have the plate in that position, the other end of it will look just like in the picture below.

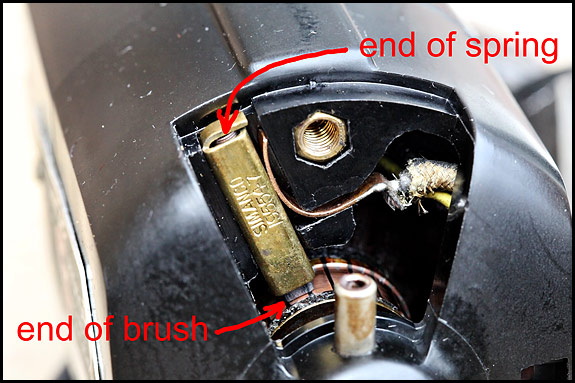

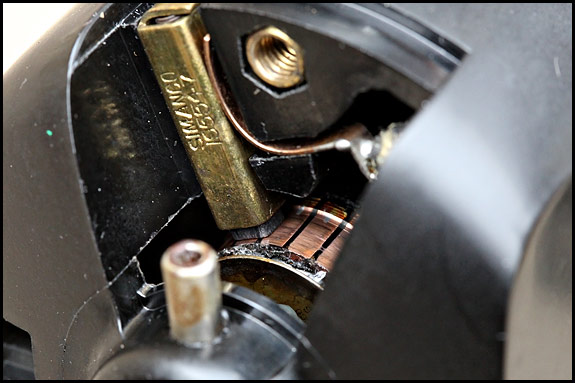

And there you finally see what holds the slide plate in! Yep, it’s that double-ended spring. See how the two grooves in the underneath of the slide plate fit over the ends of the spring? No? OK then, just for you …

Now you’ve seen that and you understand how it fits in, it won’t come as any surprise at all to find that if you push the slide plate just another 3mm or so towards the needle, the back end of it clears the spring …

Et voilà – you’ve successfully removed the slide plate of a Singer 99 (or indeed a 66 ‘cos it’s just the same)!

And at this point I should have taken another snap to illustrate why when you slide open the slide plate normally, you can’t slide if off the end of the machine. But I forgot to. No biggie though – if you turn your slide plate over, you’ll see the reason. That’s right – those grooves which fit over the ends of the spring don’t go all the way along the underneath of the plate, which is why you have to take it off the other way like you just did.

Replacing the slide plate is easy. Drop it in place (the right way round) with the end nearest the needle over the feed dogs, and line up the grooves in the other end with the ends of the spring, like this …

then wiggle it over the spring ends like this …

and then keep pushing towards the end of the machine until it drops into place. Job done!

Finally, a Dire Warning. Here’s a picture of the magic spring with that arm thingy swung out of the way so you can clearly see the screw which holds it in place …

Judging by the size of that screw head, you would think that it’s on the end of a fairly normal kind of a screw. But it is not. Oh no. Not at all. That screw is a really skinny little thing, which is very easily snapped off by the over-enthusiastic application of a screwdriver. When it snaps, it can be a real PITA to extract in order to replace it so that the spring is held in place and your slide plate will stay put.

If that spring is loose on your machine, take it very easy indeed when tightening that screw …

You must be logged in to post a comment.