DISCLAIMER – This post it not written by a professional electrician. It’s written by a retired bloke who meddles with old Singers, and what follows is nothing more than personal opinion based on experience and, hopefully, a smattering of common sense.

It might help readers to know that I grew up in a house where, as was still common at the time, all the mains sockets were 2-pin. In other words, there was no provision for earthing anything electrical. That didn’t stop Mother sometimes taking the chill off the bathroom in the winter (only on the very coldest of nights, mind – she wasn’t made of money!) with a metal-bodied single-bar electric fire placed on the floor a good 5ft away from me in the bath, its lead snaking under the door and into the 2-pin socket just inside my bedroom. Mother wan’t daft, so I never have worked out whether she was simply confident that 7 year-old me had enough sense not to splash water onto that electric fire when I got out the bath, or whether some pressing issue might have been resolved by my early demise.

Whatever, I grew up with a healthy respect for mains electricity, and have done perhaps more than my fair share of DIY home electrics. I’ve also worked for several years in the assembly of electrical and electronic products, but I reckon that’s enough background for you to decide how much notice to take of what follows.

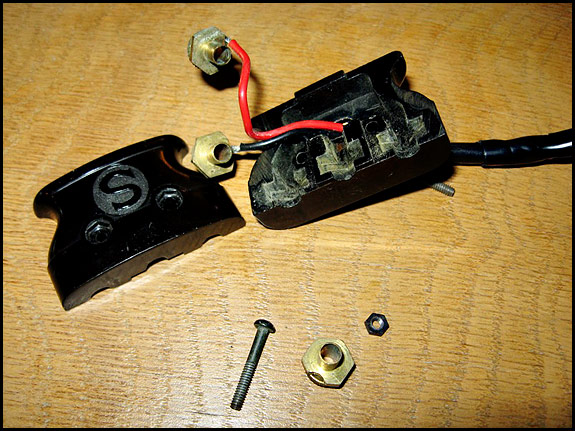

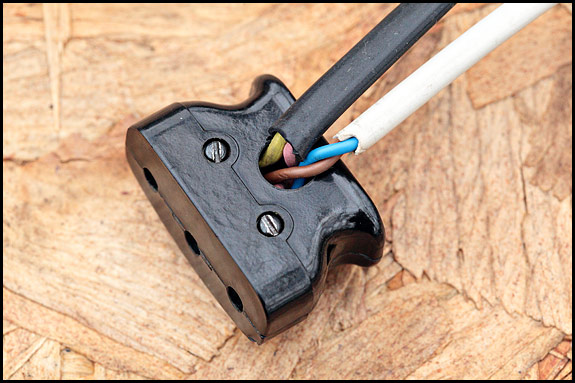

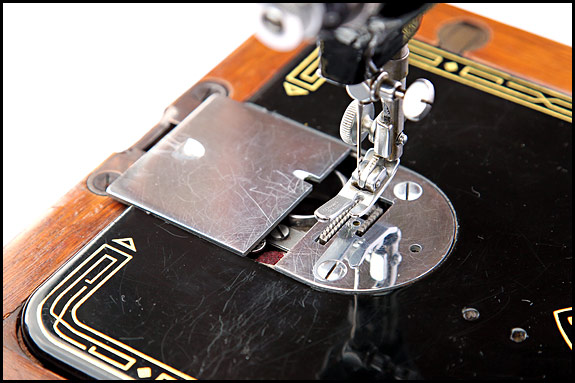

What’s prompted this post is an email I got from one of our readers asking how she should earth her Singer 201K. Specifically, the question was why, when the original 2-core lead has at some point been replaced by a 3-core one with a 3-pin mains plug on one end of it, is the earth wire not connected at the machine end? This lady kindly sent a rather good picture of what she found when she undid the Singer connector …

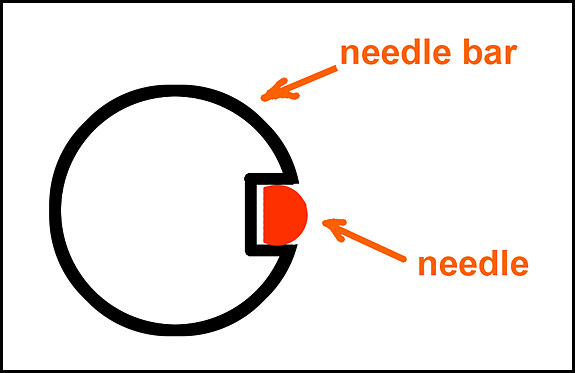

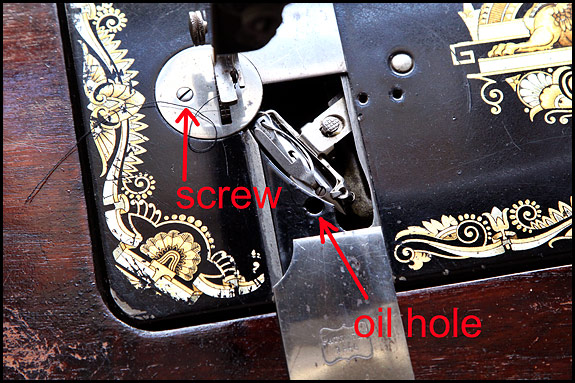

Given that there are three contacts in that connector and only the outer two are wired up, it’s entirely reasonable to suppose that the earth wire should go to the middle one. After all, that’s what you’ll find if you open up the plug on your kettle or whatever. But this is a Singer sewing machine that’s at least 60 years old. Not only were things done rather differently back then, but that machine connector’s also a bit out the ordinary in that there’s only one mains cable going to it. And the reason for that is that this particular plug goes into a 201 with a knee-lever controller. If it plugged into a machine with the usual foot-pedal controller, the wiring would be more like this …

See the red wire going to that centre terminal? That’s a good clue that it’s not an earth connection. In fact, the centre connection of these old Singer plugs goes to one side of the motor, and connecting an earth wire to that would not be a good idea, because you would in effect be connecting the live pin of your mains plug to the earth pin of it via the sewing machine motor.

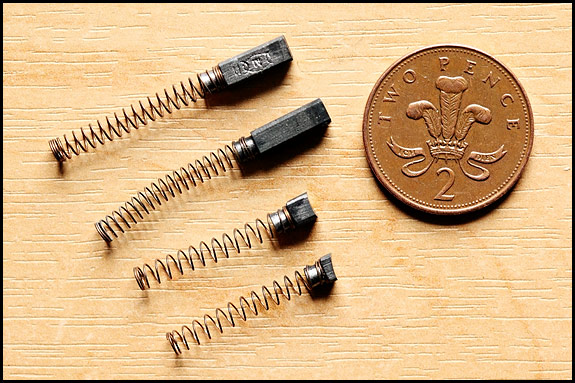

So how, you ask, do you then earth an old Singer electric? The short answer is that you don’t. You could do, but unless your foot-pedal and mains leads are permanently wired in as on the 185 and the final variant 99’s, the necessary wiring would look a mess and be a PITA if you wanted to unplug the leads from the machine.

OK then – how to avoid death by vintage Singer? In my opinion, you need to ensure first of all that when you’re using the machine, you’re plugged into house wiring which has been professionally checked within the last 10 years and has a consumer unit fitted with a good RCD. If that’s meaningless, see here

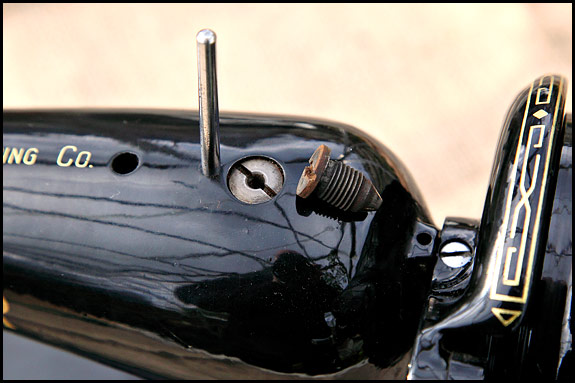

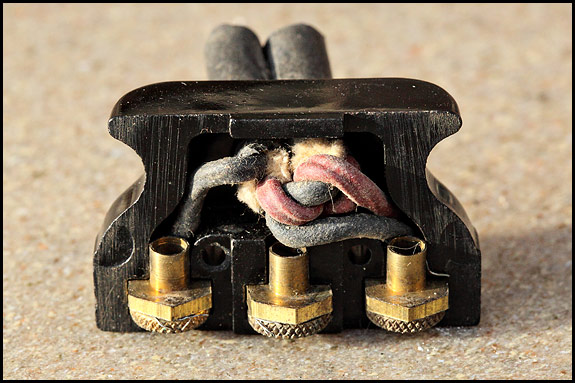

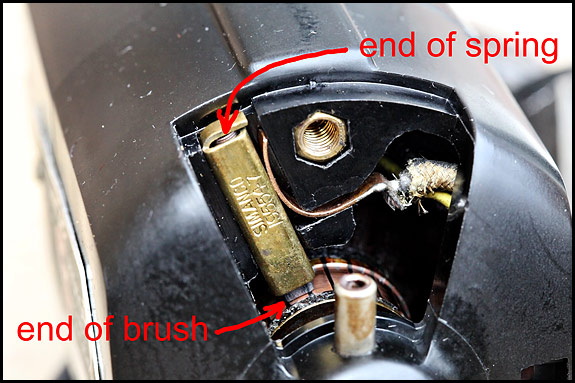

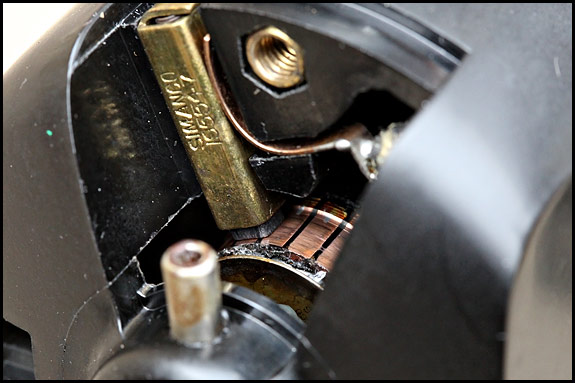

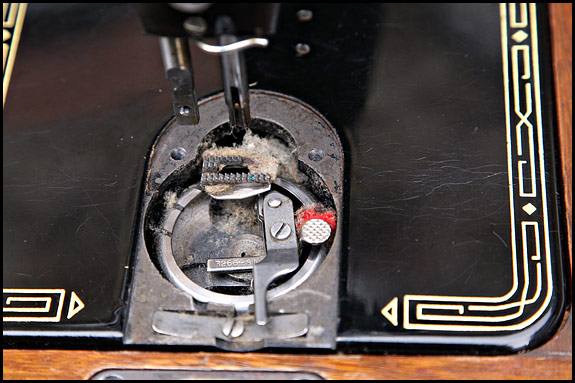

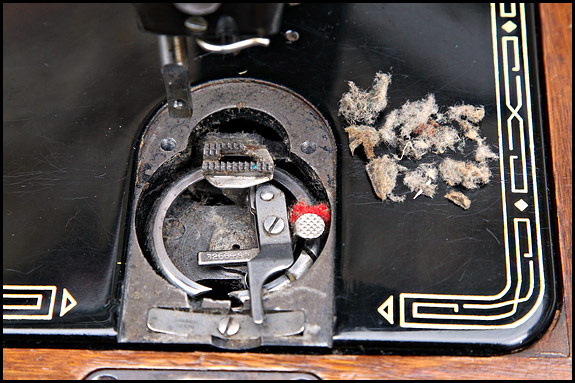

You also need to inspect both the mains lead to the machine and the lead from the foot pedal for any signs of cuts or wear in the outer covering, and while you’re at it, take a good look at any visible wiring on the machine itself. If it looks a bit dodgy, it probably is, and you need to get it sorted. Similarly, if the wiring going into your machine plug looks something like this, that also wants attending to …

And finally, you can perhaps bear in mind that until Singer started flogging machines with three-pin plugs on the end of the mains leads (towards the end of the 1960’s ?) very few domestic electric sewing machines were earthed, but even fewer users of them were electrocuted.

That’s it for this first part, but there’s more to come on this subject …

Top picture © Colette Granville, used by kind permission

You must be logged in to post a comment.